Some History and Bishops

Bishops of Dunedin

Early Controversy

The very early days of the Diocese of Dunedin got off to a rocky start with the first Bishop appointed not able to take his seat. The controversy of what happened to Henry Jenner has echoed down through the years. In August 2018 Dr Tony Fitchett gave a talk about Jenner at the Anglo Catholic Hui held in All Saints Church, Dunedin.

More Information

“May I start by thanking the organisers of this conference for asking me to speak about Bishop Jenner. I should say that I wouldn’t describe myself as Anglo-Catholic, with capital A and C, though I certainly maintain that the Anglican Communion is part of the catholic church (small ‘c’s)

I grew up in Nelson, where clerical garb for Communion services was cassock, surplice and scarf, with celebration from the northern position, and I was at secondary school in Christchurch. The only time I saw a chasuble was if we came to Dunedin on holiday. I was present when cope and mitre were worn for the first time in Nelson Cathedral, in 1965. Holy Communion in 1991 at Carrickfergus, near Belfast, was like a time warp back to 1950s Nelson.

34 years and two days ago, in the Diocesan Synod, David Best, Vicar of this parish, asked the President: “Is there any intention to instigate proceedings to enable Bishop Jenner to be formally recognised as the first Bishop of Dunedin, or any intention, in common justice, to declare him the first bishop of this diocese?”

Standing Committee had just published ‘Seeking A See’, the diary of Bishop Jenner’s visit to New Zealand in the hope of taking up the Bishopric of Dunedin.

The book’s editor, the Revd John Pearce, argued in it that Jenner was the First Bishop of Dunedin – a claim endorsed by the Bishop of London, in a Foreword to the book, and by almost all its reviewers, in New Zealand and England (though not George Griffiths in the ODT).

What was it about?

Early New Zealand Anglican bishops, from Selwyn in 1841, were appointed under Royal Mandate.

The 1857 Constitution of this Church provided that

“The nomination of a Bishop shall proceed from the Diocesan Synod, and, if sanctioned by the General Synod, shall be submitted to the authorities in Church and State in England for their favourable consideration”

In 1859 the Otago Rural Deanery Board – a sort of local synod – was established for Otago/Southland, then part of Bishop Harper’s Diocese of Christchurch.

In 1861 the Board decided to raise an endowment for a Dunedin Bishopric.

In March 1865 the Privy Council ruled that the Crown had no power to create dioceses, or appoint Bishops by Letters Patent, in colonies with an independent legislature.

In May1865 General Synod amended the constitutional provisions for appointing bishops, to:

“The nomination of a Bishop shall proceed from the Diocesan Synod, and if such nomination be sanctioned by the General Synod, or, if the General Synod be not in Session, by a majority of the Standing Committees of the several Dioceses, the senior Bishop shall take the necessary steps for giving effect to the nomination”.

General Synod also mentioned a future Diocese of Dunedin.

After General Synod , Selwyn and Harper met with the Standing Committee of the Board, and Selwyn suggested that at its next meeting the Board should ask him to write to the Archbishop of Canterbury “to know if his Grace could name an eligible person as Bishop of Otago and Southland”.

The Board discussed the matter in June, but refused Selwyn’s request, because of the lack of endowment.

But Selwyn had already written to Archbishop Longley, asking him if he knew of anyone suitable for the task. Longley responded, not by suggesting someone, but by offering the future bishopric to Henry Jenner, Vicar of Preston-by-Wingham, and Minor Canon of Canterbury Cathedral, who accepted.

Jenner was well connected, had read law at Cambridge, played cricket for Cambridge and the Gentlemen of Kent, founded the Choral Union of the Cathedral, was secretary of the Ecclesiological Society, and had written a pamphlet about ensuring a supply of flowers of appropriate liturgical colours for decorating churches, by encouraging rich parishioners to grow them in their hot-houses.

Selwyn accepted Longley’s action, but the Board didn’t. It resolved not to accept Jenner, because of the lack of endowment and the bypassing of its authority. However Harper, who wasn’t present, vetoed the resolution, and it never reached Jenner.

The Archbishop already had someone to consecrate as a bishop for New Zealand – Suter, to be second Bishop of Nelson – so on August 24th Longley consecrated them both, in the case of Jenner “into the office of a Bishop in the United Church of England and Ireland in the Colony of New Zealand”.

Faced with this the Board gave in, and resolved to “recognise the duty of making preparations for his reception”.

It apparently also received reports of Jenner’s “High Church views and ritualistic practices” but expected Jenner to arrive soon, and had doubts about the reports.

More on the Oxford Movement

During the second phase of the Oxford Movement, following Newman’s move to Roman Catholicism, some Anglo-Catholic priests began using liturgical ritual to emphasize the importance of the Eucharist, and this triggered sometimes bitter opposition.

In the late 1850s and early 1860s there were riots in some churches in the East End of London, such as St George’s-in-the-East, ostensibly protesting about such “popish” innovations as vestments, mixing water with the wine for Communion, wafers rather than bread, making the sign of the Cross, elevating the host, the eastern position, and having candles burning on the altar, but probably organised, through a sort of rent-a-mob, by exploitative East End employers, whom the hardworking East End clergy had denounced, and publicans and brothel-keepers whose trade was affected by the social work of the clergy.

One of Bryan King’s curates at St Georges, later, when at St Alban’s Holburn, was prosecuted in a series of cases that went all the way to the Privy Council, and another priest, in 1877, was imprisoned for contempt of Court when he disregarded the orders given at a trial under the Public Worship Regulation Act 1874.

Ritualism triggered high feelings, in Jenner’s time, as the ordination of women did in the late 20th century, and same-sex relationships do now. Riots occurred in some English churches, and clergy were prosecuted and even imprisoned under Britain’s Public Worship Regulation Act.

Concern about Jenner’s churchmanship didn’t subside.

In September 1867 a letter in the Guardian drew attention to a Memorial to the Archbishop, instigated by the Vicar of Riverton, complaining that the appointment was made against the Board’s wishes, and that, as Jenner had identified himself with the Ritualistic Party, ‘the peace and harmony of the proposed new diocese would be destroyed, and great numbers of most earnest members alienated from the church by the presence of such a chief pastor, and … the work of the Church in these provinces would be hindered if not brought utterly to a standstill.”

Jenner responded at length, and in October William Carr Young, a Dunedin churchwarden, Lay Reader, and member of the Board, who visited England that year and in May attended the “Feast of Dedication” at St Mathias, Stoke Newington, in which Jenner took part, wrote in reply. He was shocked by the robed procession, candles, and other High Church ritual [see SaS, p.69] he saw at St Mathias. He met Jenner and the Archbishop, and wrote to New Zealand about Jenner’s “extreme views and practices”.

A long correspondence between Jenner and the Archbishop ensued.

Jenner denied any intention of introducing ritualism to Dunedin, writing to the Board in July that “Nothing, in my opinion, would be more ridiculous than to attempt to carry out “high ritual” in New Zealand, particularly in such a settlement as that of Otago.”

The Board responded, voting 12 to 9, that “this Board does not feel justified, in the fact of the assurance, in endeavouring to dissuade the Bishop from taking charge of the See” .

In July the Board resolved that the question of the formation of the diocese, and the appointment of a bishop, should be referred to the General Synod. Some members wrote to Harper saying they had no confidence in Jenner’s promises.

At the 1868 General Synod, where the future diocese was represented by clergy and lay reps, a Committee considered those matters, and reported that because of the inadequate endowment, and the likelihood that arguments about Jenner would affect fund-raising, his appointment shouldn’t be confirmed.

Jenner had written to the General Synod, claiming that a contract had been entered into between the NZ Church, acting through Selwyn, and him, but it was pointed out, during a bitter debate, that no-one had the right to pledge the faith of General Synod.

General Synod finally resolved “That whereas the General Synod is of the opinion that it is better for the peace of the church that Bishop Jenner should not take charge of the Bishopric of Dunedin, this Synod hereby requests him to withdraw his claim to that position.”

It also passed a statute constituting the Diocese of Dunedin, to take effect on January 1st 1869, and providing that the Bishop of Christchurch was to have charge of the new diocese “until a day fixed by the Standing Commission”.

At the beginning of 1868 Jenner felt that opposition to him was waning, and he should come out to New Zealand, but he waited till after General Synod. He arrived in Wellington on January 27th, 1869, the same day the ODT reported a sermon of his, in which, comparing the Evangelical and Catholic movements, he “gave expression to some very advanced doctrines indeed”.

He came to Dunedin via Lyttleton, but did not go to Christchurch to see Harper. He travelled throughout the diocese, though, speaking at many meetings, and received a mixed reception. St Paul’s was supportive – Jenner got on well with the vicar and choir, and later gave a public lecture on church music, with illustrations by the choir. Invercargill, initially hostile, was won over, but some parishes firmly rejected him. And debate continued in the papers.

The Diocesan Synod convened for the first time on April 7th 1869, Bishop Harper presiding.

A long motion was moved in support of Jenner, stating that his appointment should be confirmed unless it could be proved that he’d been unfaithful in doctrine or discipline, and asking the Standing Committees of the dioceses to sanction the appointment if no charge was brought and proved within three months.

Debate began at 8.00pm on August 8th, and continued through the night till a division was taken at 6.00am on the 9th.

The clergy voted 4 to 3 for the Motion, but it was lost 10 to 15 in the house of laity, and a move to refer the matter to the Archbishop of Canterbury failed.

Jenner left for home on May 15th 1870 (he hadn’t resigned his living at Preston), but argument continued in the ODT and the Otago Witness.

In 1870 the Archbishop of Canterbury, Dr Tait, after discussions with Jenner and Selwyn, wrote a so-called ‘Judgement’ which, though admitting he’d heard only one side of the case, gave his opinion that Bishop Jenner “has an equitable claim to be considered Bishop of Dunedin”. Tait advised Jenner to forgo his claim, but Jenner wasn’t prepared to.

So General Synod in 1871 passed a motion which concluded “That … whereas the law of the Church requires the sanction of the General Synod to the nomination of a bishop to any See in New Zealand, … this Synod does hereby refuse to sanction the nomination of Bishop Jenner to the See of Dunedin, whether that nomination were in due form or otherwise. But at the same time this Synod begs to express its sympathy with Bishop Jenner in the painful position in which he has been placed.”

The Diocesan Synod didn’t address the matter of a bishop in 1870, but in 1871 it nominated Samuel Tarratt Nevill to be Bishop of Dunedin.

He had doubts, not least because of Tait’s statement, but was reassured by Sir William Martin that Bishop Jenner had never been appointed Bishop of Dunedin, and “if I did not accept he was now probably the last man who would be asked to do so.”

He was consecrated, and enthroned on June 4th 1871.

Jenner purported to resign the see on June 16th, but never relinquished his claim to have been the First Bishop of Dunedin.

Bishop Abraham, who’d joined Selwyn at Lichfield, wrote to the Guardian in 1871, supporting Jenner’s claim.

Canterbury and other English bishops agreed with Jenner, stating in 1872, and again in 1874, that they would recognise Nevill as Second Bishop of Dunedin.

In 1872 Jenner published a pamphlet in support of his claim

“The See of Dunedin, NZ, The Title of The Rt Rev HL Jenner, DD, to be accounted the First Bishop, briefly vindicated.”

During the 1874 General Synod a Select Committee reported on the grounds on which the Synod had acted regarding the Bishopric of Dunedin, and Synod resolved that:

“… Dr Jenner, not having been appointed to the See of Dunedin in accordance with the laws of the Church in New Zealand, ought not to be recognised as having been the first such bishop; and this Synod does recognise the Right Rev Samuel Tarrat Nevill, DD, as the present and First Bishop of Dunedin.”

In 1874 Henry Jacobs, Dean of Christchurch, who’d attended the relevant General Synods, published a rebuttal of Jenner’s pamphlet and Abrahams’ letter.

In 1924 by Henry Lowther Clarke, in his authoritative “Constitutional Church Government in the Dominions Beyond the Seas”, agreed with Jacobs.

Sixty years later Bishop Mann concurred, noting that Jenner’s alleged appointment had never been sanctioned, and he had never been enthroned, so he’d never been Bishop of Dunedin, but, like the 1871 General Synod, Bishop Mann sympathised with Bishop Jenner.

“The tumult and the shouting dies …” But, “Lest we forget …”

We Love The Place O God (Tune – Quam Dilecta) (click on this link for Youtube version of this hymn)

Tune composed by Henry Lascelles Jenner.

This drawing by William Burges, from the Canterbury Cathedral Archives, illustrates a crozier – a staff carried by bishops as a symbol of their office – featuring George and the Dragon. The real crozier now belongs to the Bishops of Dover, but is kept at Canterbury Cathedral (pictured). Made for Henry Jenner in the 1860s – when he was appointed Bishop of Dunedin in New Zealand – it was designed by William Burges, who was the architect of the Maison Dieu in Dover.

The head of the crozier features St George dressed as a knight, killing a dragon, above a long-haired female figure bound captive.

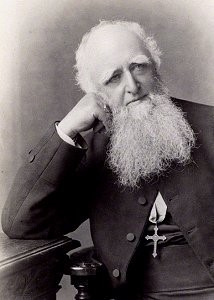

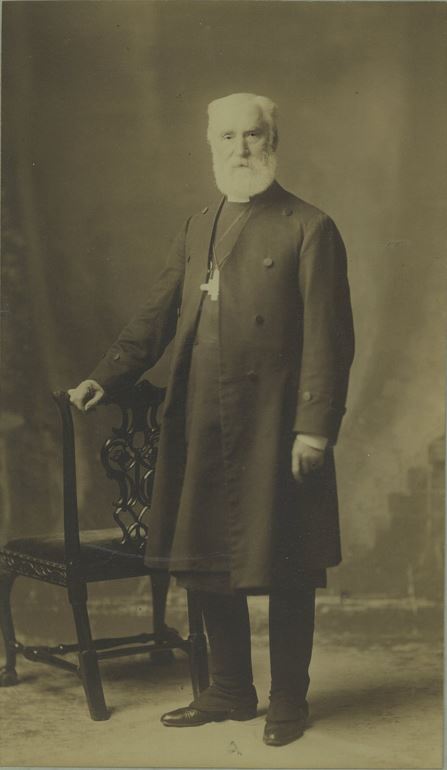

Bishop Samuel Tarratt Nevill

1870 – 1919

Samuel Nevill was born on 13 May 1837 in Nottingham, England, one of six children of Mary Berrey and Jonathan Nevill.

Samuel Tarratt Nevill was born on 13 May 1837 in Nottingham, Nottinghamshire, England, one of six children of Mary Berrey and her husband, Jonathan Nevill, a hosier. From an early age he desired ordination, but was unable to pursue this until 1858, when he received a legacy from his grandfather. He attended St Aidan’s Theological College, Birkenhead, and for one year only enrolled as an extramural student of Trinity College, Dublin. He was ordained deacon in 1860 and appointed curate of Scarisbrick in the parish of Ormskirk, Lancashire. While there he met Mary Susannah Cook Penny of Heavitree, Devonshire, and married her on 3 July 1862 at Heavitree. She had substantial private means, which was to be of great importance in some of Nevill’s schemes.

Nevill was ordained priest in 1861, and matriculated, probably in 1862, for the University of Cambridge. He became a fellow-commoner of Magdalene College, graduating BA with second-class honours in the natural science tripos in 1866 and MA in 1869. He became rector of Shelton, Staffordshire, in the diocese of Lichfield, in 1864. George Selwyn, bishop of New Zealand and from 1868 bishop of Lichfield, offered in early 1870 to suggest Nevill’s name for the vacant diocese of Wellington, New Zealand. Nevill demurred, but accepted Selwyn’s suggestion that he visit New Zealand, where his wife had brothers living. The Nevills arrived in New Zealand, having travelled overland across the United States, on 13 September 1870.

More Information

Nevill attended the General Synod of the Anglican church in Dunedin in February 1871. The Dunedin diocese, newly established in 1869, was still racked by the controversy over its refusal to accept Henry Jenner as its first bishop. Nevill, when approached, indicated that if Dunedin were to nominate him as its first bishop he would accept. He was duly nominated and accepted, and was consecrated on 4 June 1871. In recogniton of this he was awarded an honorary DD by Cambridge university in 1872.

The diocese of which Nevill found himself bishop was small and scattered, and chronically short of funds, but now had a bishop who was determined, energetic and visionary. Despite difficulties, the Anglican church in Otago and Southland expanded significantly during his time, from 10 clergy and 14 churches in 1871 to 43 clergy and 75 churches in 1919, and the diocese became well organised. It could not at first afford to build a house for the bishop, and when he built his own the diocese was often in arrears on the agreed rent. Nevill built Bishop’s Court in Roslyn, Dunedin (now part of Columba College), and then Bishopsgrove in Leith Valley.

Lack of funds never daunted Nevill. High on his list of priorities was a theological college to produce local clergy. The diocese was very lukewarm about the project, but eventually endorsed it in 1887. While at the Lambeth Conference in 1888 Nevill sought books and money for the college, and on 25 January 1893 Selwyn Theological College was opened as both a theological college and hall of residence for the University of Otago.

Nevill was committed to the church’s role in education, and deplored the confining of teaching to such things ‘as would prove of advantage in mercantile and materialistic concerns’. Having been impressed with the educational work of the Community of the Sisters of the Church in Kilburn, London, he invited them to found a school in Dunedin. St Hilda’s Collegiate School opened on 1 February 1896. It grew rapidly, and until 1904 was the only Anglican school for girls in New Zealand. Nevill was less successful in founding a boys’ school, although he made some attempts.

Another of Nevill’s concerns was the social work of the church. He established the Brotherhood of St Andrew to support the work of the Reverend V. G. B. King as visitor to the public institutions in the diocese, and in 1902 he set up the Deaconess Institute to manage St Mary’s Orphan Home for Girls, which Mary Nevill had begun in 1883 in the grounds of Bishopsgrove. Nevill did not support the contemporary demand for prohibition, regarding drinking as a matter of personal self-control.

The bishop was determined to have a cathedral, and raised the issue in synod in 1876. The diocese was unenthusiastic. Nevill returned to the subject repeatedly, but the various schemes suggested came to nothing until 1894 when it was finally agreed that St Paul’s Church in the Octagon should become the site of the cathedral. A substantial bequest in 1904 from the estate of William Harrop speeded the process of fund raising. Nevill laid the foundation stone of the new cathedral on 8 June 1915, and the building was consecrated on 12 February 1919. Even so, Nevill’s grandiose plans were only one-third completed, and then only after wrangles between the parish of St Paul’s and the bishop and cathedral chapter.

Samuel Nevill was a man of firm opinions vigorously expressed. He wrote a number of pamphlets, mainly on church matters, engaged in debate on contemporary issues in the letters columns of the local newspapers, and retained his scientific interest through membership of the Otago Institute. His relations with his clergy and others were sometimes strained. He strongly defended the autonomous rights of individual national churches of the Anglican communion, but was also committed to the extension of New Zealand’s influence in the Pacific. In this he had little support from his fellow bishops, although the inclusion of the diocese of Polynesia in 1925 as part of the New Zealand Anglican province owes something to him.

On 1 February 1904, already acting primate by virtue of his seniority, Nevill was elected primate of New Zealand. In acknowledgement of this his old college made him an honorary fellow in 1906. In the same year he was created a sub-prelate of the Knights Hospitallers of the Order of St John of Jerusalem.

Nevill’s first wife died on 27 November 1905, and on 25 September 1906, while in England, he married Rosalind Margaret Fynes-Clinton at Blandford, Dorsetshire. Rosalind was his wife’s young companion and daughter of the vicar of Waitaki mission district. There were no children from either marriage, but several nieces and nephews were brought up by the Nevills. At the end of 1919, Nevill, now the senior bishop not only of the Anglican church in New Zealand but of the whole Anglican communion, retired. He died at Bishopsgrove on 29 October 1921, and was buried in accordance with his wishes in the churchyard at Warrington, near Dunedin. Rosalind Nevill died on 23 April 1972.

Information is taken from an article in the Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

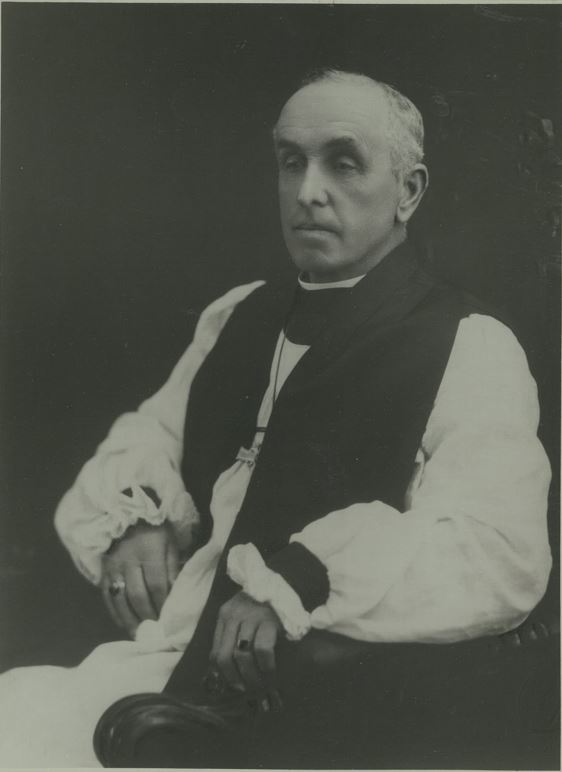

Bishop Issac Richards

1920 – 1934

According to Wikipedia, Isaac Richards was educated at Exeter College, Oxford and ordained in 1882.

The second Bishop of Dunedin Isaac Richards did not stay in post as long as Bishop Nevill, but was possibly less controversial.

According to Wikipedia, Isaac Richards was educated at Exeter College, Oxford and ordained in 1882. He was curate of St Paul’s Truro then vicar of St Mark’s Remuera. In 1895 he became Warden of Selwyn College, Otago. Later he was Archdeacon of Invercargill, a post he held for 11 years before being appointed Bishop of Dunedin from 1920 to 1934. Isaac was also the Chaplain at St Hilda’s for 38 years. Sadly, he had two sons were killed at Gallipoli … one on April 25th, with the other dying of his wounds a week later, One of the stained glass windows in St Hilda’s Chapel is in memory of them.

Isaac was also a cricketer, playing first class matches for Auckland in the 1890s. He died in 1936 in his 78th year.

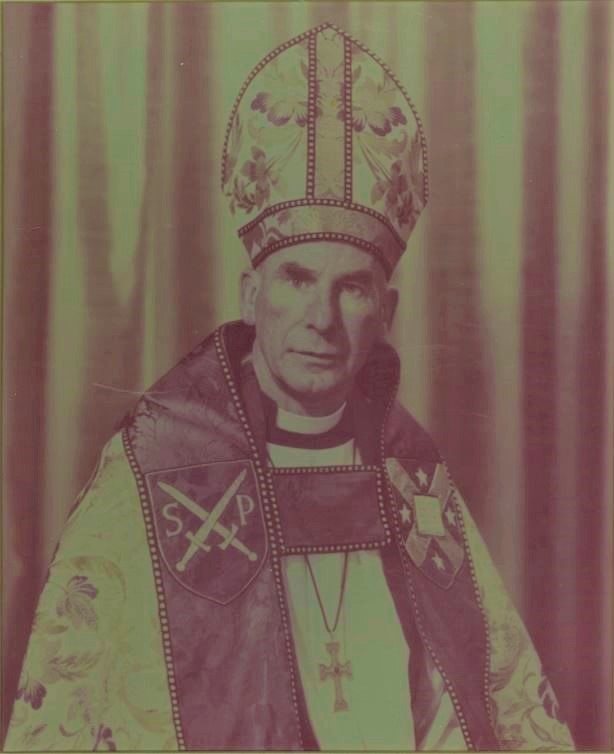

Bishop William Alfred Robertson Fitchett

1934-1952

Alfred Fitchett was born in Christchurch and his father was the Very Reverend Alfred Robertson Fitchett CMG of Dunedin.

He was educated at Otago Boys’ High School and Selwyn College, Cambridge.Ordained in 1901, he was curate then priest in charge of St Thomas’ Wellington before being vicar of Dunstan and Roslyn. In 1915 he became the Archdeacon of Dunedin, a post he held for 19 years before being appointed its Bishop. Fitchett was awarded the King George V Silver Jubilee Medal in 1935.[7]

Rev’d Bernard Wilkinson asks:

Are there any left in the diocese who remember the time when Bishop Fitchett, at a service in the old S. Luke’s. Mosgiel, which had a very tiny sanctuary, bent bowed low to the altar – and the tassel on his mitre caught on fire from the candles?!

We are not sure if anyone else remembers, but suspect that Bernard may be one of the last people in the Diocese to have a living recollection of Bishop Fitchett.

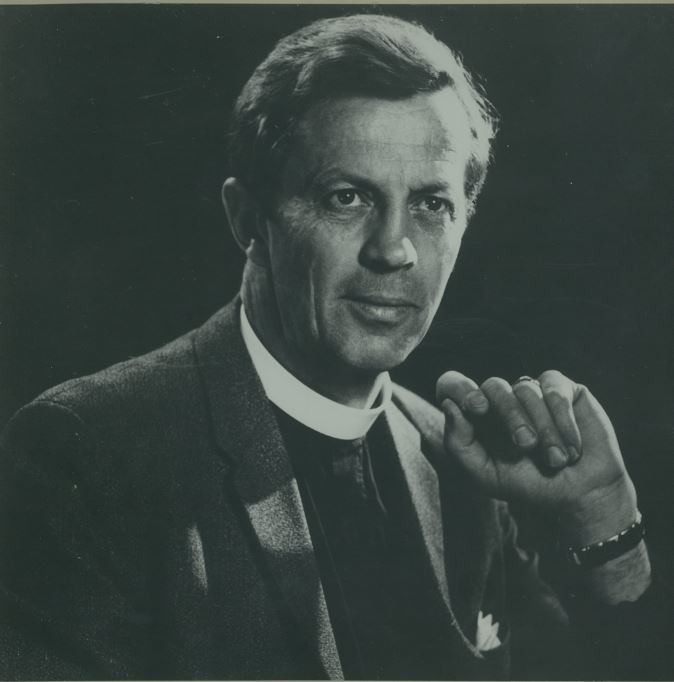

Bishop Allen Howard Johnston

1953-1969

Allen Johnston was born in Auckland, New Zealand. He had an enormous influence within the Diocese and throughout Aotearoa – NZ.

He was educated at Seddon Memorial Technical College and St John’s College, Auckland before beginning his ordained ministry with a curacy at St Mark’s Remuera. He then had incumbencies at Dargaville, Northern Wairoa and Otahuhu. In 1949 he became Archdeacon of Waimate, a position he held for four years before being appointed the Bishop of Dunedin. He was translated to be Bishop of Waikato in 1969 for 11 years and was additionally elected Archbishop of New Zealand in 1972.

After his retirement he continued to fill in as priest-in-charge at several parishes around Waikato.

He served as a member of the Royal Commission to Inquire into and Report upon the Circumstances of the Convictions of Arthur Allan Thomas for the Murders of David Harvey Crewe and Jeanette Lenore Crewe

He was widely regarded as a wise leader who saw the Anglican Church through a period of change in the 1960s and 1970s. His son-in-law, the Reverend Dr George Armstrong, said Archbishop Johnston was never afraid of change “where it was appropriate. He took a strong, clear and high-profile lead in building relationships between the churches and the church union movement.”

He was also a great advocate of allowing women to be ordained priests into the Church.

More Information

We have some further memories of Bishop Johnston from the Venerable Bernard Wilkinson and the Rev’d David Crooks

The Venerable Bernard Wilkinson has shared the following memories:

Allen Howard Johnston 1953 – 1969

Bishop Allen` Johnston came to us from the parish of Whangarei. At his welcome in Invercargill he said that he had come from the furthest north of NZ to the furthest south. It is worth noting that he was the first student of S. John’s Theological College in Auckland to be elected a Bishop – our first New Zealander.

Aged 40 at the time of his election, the new Bishop faced issues within the diocese with determination. One of his first concerns was the shortage of clergy – at his first Synod he had to report that seven parishes were without vicars. Moreover, there were only two assistant curates in the diocese, which could be looked to to take charge of parishes. Another issue which the new Bishop faced head-on was the abysmally low level of clergy stipends. In the first seven months of his episcopate he visited every parish and vestry, setting before them the simple facts of finances. The response was encouraging – twenty one parishes increased stipends before Synod. The decision of some parishes to employ the Wells Fundraising Organisation undoubtedly helped. He was also instrumental in setting up the Anglican Church Pension Board, and his concern for the care of his clergy was well known.

The 1950s were a time when things were prospering – and so was the Anglican diocese. During Johnston’s episcopate parishes expanded, many new churches were built, and new vicarages or replacement ones built. Macandrew Bay, Heriot, Oturehua, Gore (to replace the church and hall destroyed by an arsonist), North Invercargill, Pine Hill, Waverley, and Halfway Bush , Alexandra, Cromwell, Queenstown, Riverton, Gore. New churches were built at North East Valley, Ranfurly, Lumsden, Balclutha, Clinton. Facilities were built for the construction villages at Roxburgh Hydro, and later at Otematata.

To match the new accession of material wealth there were also clear signs of spiritual progress – for between 1954 and 1966 the number of communicants at Easter rose by 25%. Yet the census figures reveal that Anglicans were becoming a decreasing proportion of the total population of the diocese.

In 1963 what came to be known as the Plan for Union was emerging – the proposal that the Anglican, Presbyterian, Methodist, Congregational and Church of Christ should combine. Bishop Johnston was deeply involved in the negotiations, and without a doubt was himself well committed to the concept. His enthusiasm was not shared by all clergy or people, as we shall see in the record of his successor. Equally, he was dedicated to the ordination of women and before he retired he had the satisfaction of ordaining a number of women candidates for the ministry.

When we look back over the three episcopates since the formation of the diocese, it would seem that Bishop Nevill was a visionary bishop. Bishop Richards could be described as a gentle Bishop. Bishop Johnston was without doubt a statesman Bishop. In time he become a world figure in church affairs, being elected as one of the Presidents of the World Council of Churches. In 1968 he attended the Lambeth Conference in Canterbury – and there will be some in the diocese who remember the welcome home accorded to him in the old Town Hall Concert Chamber. In the days before air travel and internet, he was sometimes absent overseas for long periods, yet he always had his finger on the pulse of the diocese.

In 1969 the electoral Synod of the diocese of Waikato chose him to be their new Bishop. The sixteen years of his leadership had seen remarkable growth in all areas of church life. In time he was elected Archbishop of New Zealand, an office he held for eight years till he retired He eventually retired but continued serving the church as locum when needed. The honour of CMG was conferred upon him by H.M. the Queen.

At one stage. after retirement, he served as a commissioner in the Royal Commission into the Arthur Alan Thomas affair.

He died in Hamilton in 2002, a faithful servant of God and His church.

Rev’d David Crooke reflects more on the life of the Right Rev’d Allen Johnston, the fourth Bishop of Dunedin.

On 26 January 1954, H.M. the Queen was welcomed to Dunedin at a Civic Reception. Sitting below the organ above the Town Hall stage, were two young Bishops.

Allen Johnston was only 42 years old and had become our Bishop the previous year. He was the first NZ educated Anglican Priest to become a Bishop in this country.

The Bishop, his wife Joyce and the four daughters came from Whangarei, where Allen Johnston, and a team of clergy, served the largest number of parishioners in any parish in NZ at that time.

The other Bishop in Dunedin at the Civic Reception was John Kavanagh, six months younger in agethan our Bishop. Dr. Kavanagh trained for the Roman Catholic priesthood at Holy Cross seminary in Mosgiel, before achieving two doctorates in theology in Rome.

In 1949, Dr Kavanagh was only 36 years old when he was consecrated to be a “bishop in waiting” to the RC Bishop of Dunedin, Bishop Whyte. The latter spent nine years in hospital care, after suffering a severe stroke. John Kavanagh only succeeded to the RC See of Dunedin in 1957, when Bishop Whyte died.

Allen Johnston and John Kavanagh were similar in temperament, both being reserved rather than outgoing. Both men became extremely able chairmen.

In this respect, in the first Lambeth Conference in 1958, our Bishop, from a Diocese so far from Canterbury, was noticed by Archbishop Fisher. At the next Lambeth Conference in 1968, Bishop Johnston was chosen to chair one of its most important committees.

As the Ven Bernard Wilkinson has pointed out, Allen Johnston played a major part, not only in the National Council of Churches, but also at Assemblies of the World Council of Churches.

As the years passed, the mana of Bishop Johnston (Archbishop from 1972-8) increased, because he actively canvassed the view of others, never made a major decision without consultation and spoke about difficult issues with both clarity and brevity.

HM Queen Elizabeth II made the Archbishop a Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George, not so much for his service to the Church and nation in New Zealand, but for his role in the Commonwealth (in Melanesia), in the Anglican Communion and beyond.

As chairman and negotiator, Bishop Kavanagh also stood out for his remarkable ability. It was Dr. Kavanagh who steered the R.C. Schools into partnership with the Government’s education system. This became a win for the formerly privately Church run schools like St Hilda’s Collegiate.

For Bishop Kavanagh, the spokesperson for the other RC bishops in NZ, negotiations in Wellington were long and arduous. The outcome was surprisingly favourable for Roman Catholicism in NZ in terms of Government funding for schools. The Roman Catholic Diocese has always remembered its debt to Bishop Kavanagh, and it is good for us to also remember the profound legacy of Archbishop Johnston for the Diocese of Dunedin.

Otago University Connections

Having stolen a march on the Presbyterian establishment in the University of Otago, Bishop Nevill founded Selwyn College as a residential Anglican Theological College in 1893. In 1900 Holy Cross, Mosgiel was founded by the national seminary for the training of Roman Catholic Priests. Knox College did not open for the training of Presbyterian clergy until 1909.

Whereas Bishop Neville was never invited to sit on the Council of the University of Otago, Bishop Johnston, with only an L.Th. to his name became a valued member of the Council.

Allen Johnston may well have become the next Chancellor of the University had he not become Bishop of Waikato in 1969. That was the year the University celebrated its centennial. As a mark of our University Council’s esteem for our departing bishop, Allen Johnston received his first degree, and honour LLD (Doctor of Laws).

In those days, anyone could attend a University Graduation in the Town Hall. I was 23 years old at the time and didn’t drive. While walking down Lynwood Avenue I was startled when the Bishop stopped to offer me a lift. This had never happened before.

I squeezed into the back seat of his car, beside the Bishop’s formidable daughter, Jocelyn, and her equally formidable husband, The Rev’d George Armstrong. In front, between the Bishop and Mrs Johnston, a red doctorial gown was draped over the seat.

On that occasion, and for many years afterwards, the University Orator (he gave the resume of Bishop Johnston’s career), was Professor Alan Horsman, who died on July 21st 2019 at the age of 100.

May Allen and Alan rest in peace.

For more of the Archbishop, see

Responsibility Christian in church and society today, an anthology of readings by Allen H Johnston. ACANZP 2010.

Bishop Walter Wade Robinson

1969 – 1975

Walter Robinson (10 December 1919 – 6 October 1975) was an Anglican priest in the second half of the 20th century.

Robinson was educated at the Cathedral Grammar School, Christchurch and Canterbury University before his ordination in 1943. He was curate of St Mary’s Timaru and then of St Gabriels, Cricklewood. He then had incumbencies at Linwood and Viti Levu West. Later he was superintendent of the Indian Mission in Labasa and general secretary of the New Zealand Anglican Board of Missions. In 1969 he was appointed Bishop of Dunedin. Walter was also an accomplished singer (soloist). He died in office in 1975 in his 57th year.

Rev’d Bernard Wilkinson recalls:

Bishop Walter Robinson came to S. Luke’s (Oamaru) for confirmation. Although I wasn’t there at the time, I am told that while the choir and clergy were assembling in the crypt before the service, the Bishop, in a playful mood, took off his mitre, put it on the head of one of the choirboys, and said “Now who’s going to be the next Bishop ?” The next day Walter died.

More Information

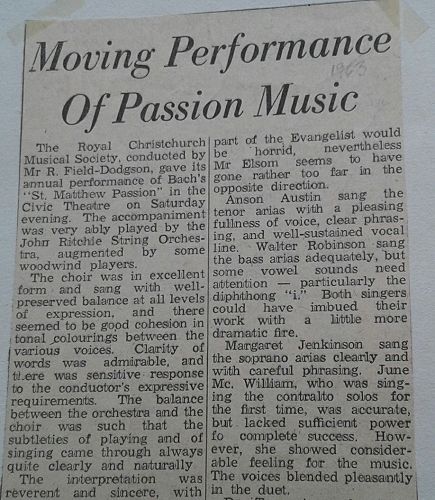

Judy Bellingham has some recollections from a friend in Christchurch about Bishop Walter’s singing career (with some reviews from the Christchurch Press attached below):

“I remember him singing with the Royal Musical Society in his purple shirt and dog collar in what must have been my first concerts. I joined the choir just as I was leaving school at the end of 1962. From then on for the next 28 years I kept scrapbooks so I was able to find the enclosed newspaper articles which are dated 1963. Obviously I have no knowledge or record of his work with the choir in 1950. I don’t think he sang with us again after 1963”.

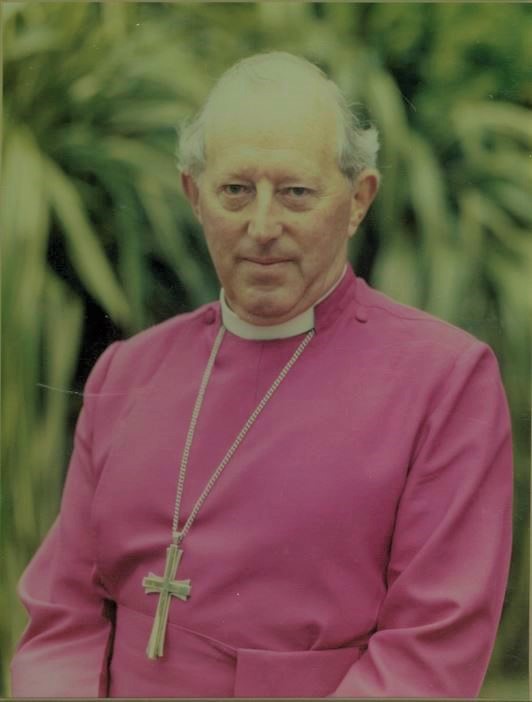

Bishop Peter Woodley Mann

1976 – 1990

Peter Mann (25 July 1924 in Perth, Western Australia – 24 August 1999 in Dunedin) was the sixth Anglican Bishop of the Diocese of Dunedin in Dunedin, New Zealand.

Peter Mann was educated at Prince Alfred College, Adelaide and St John’s College, Auckland before being ordained in 1954. He held curacies at Waiapu and Rotorua before holding incumbencies at Porangahau and Dannevirke. Later he was Archdeacon of Blenheim, Marlborough and Timaru before his ordination to the episcopate). He was survived ny his wife Anne who passed away on 18 May 2020 at the age of 96.

More Information

Bishop John Buck (who was Anne’s Nephew) writes:

Anne Mann, widow of Bishop Peter, died in Warkworth on May 18. She was 96, and up till very recently had been leading a full and active life devoted to her three daughters, Victoria, Clarissa and Teresa and their families.

She worshipped at St Leonards in Matakana where a small family funeral was held for her.

Anne was a nurse and a flight attendant in the early days of international air travel out of Australia. After marrying Peter in Napier, he was the curate, she sang in the choir, they served in parishes from Rotorua to Porongahau, Danniverke, Lower Hutt, Blenheim, Timaru and finally for 14 years in Dunedin. Anne was also the sister of Bishop Edward Norman of Wellington.

A woman of great faith, she was much loved by many around New Zealand. A memorial service will be held for her in Dunedin at a later date when her ashes will be interred alongside Peter’s at the cathedral.

Molly Fulton writes of Anne (and Peter):

I was very sad to hear that Anne Mann had died. Many people have recollections of +Peter. I have happy memories of Anne. What a supportive wife and wonderful Bishop’s wife. Every year they had the Synod reps to their home for a meal at some stage during the course of Synod. These were a great success and meant that so many could enjoy their hospitality and their wonderful home at 10 Claremont St. When I became Diocesan AAW President Anne, as Bishop’s wife, was happy to be an honorary member of our executive. She was so supportive and came to many of our executive meetings and area days.She often came up with some different angles of looking at activities. A dearly loved couple. May she Rest in peace.

Rev’d Barbara Dineen has the following memories of Bishop Mann:

“I have the warmest memories of Plus Peter, as he was known! He served in the Australian navy during World War II and he had a vast storehouse of amusing anecdotes, with which he frequently began his sermons. His memory for names was impressive, and all ladies were always greeted with a ‘Hello, dear’ and a kiss. He truly was a people person. He engaged with the city, to the point of living the gospel very visibly: he, and several of his senior clergy, marched with us against the Springbok Tour in 1981. Peter Mann was truly a man of God. His wise and gentle influence in this diocese was a great blessing.”

Rev’d Bernard Wilkinson also has some more humourous memories …

Many years ago it snowed at Synod time, and roads were blocked. This year Synod was at the Cathedral. After the service, Peter asked me if I was heading up to Roslyn (which I was). He also wanted to get up the hill to Roslyn – but he didn’t have his car. Could he have a ride up Stuart St ? Of course – but alas, the road was heavy with thick snow and many cars were marooned. I told Peter that if he liked to sit on the bonnet to give traction, I thought we could make it. And we did – slowly plugging up the hill, the Bishop waving to stranded cars. So we both arrived safely at our destinations.

It made the ODT newspaper later on !

Then there was the time the Rev Ken Light was instituted at Balclutha. During the course of the service the Bishop was supposed to hand him his Licence – but alas, he had forgotten to bring it.

At the function afterwards, the Bishop apologised for the absence of Anne, his wife, due to some other commitment. The remark was made that we were glad to know why she wasn’t there – for a moment we wondered if he had forgotten to bring her.

Peter could always take a joke against himself, and enjoyed it.

Alice Gallaway recalls:

Bishop Peter was a wonderful man. He was so kind, so there, so genuine, wise and present. Peter and his beautiful wife Ann were such a big part of our Dunedin lives. They were dear friends of my mother and father and hosted wonderful dinner parties. I remember Mum and Dad staying in bed just that little bit longer after a night there. My memories of Peter, Ann and his family are seamlessly interwoven into the happiest memories of my Dunedin family church times and celebrations

Barry Entwisle writes:

I first met +Peter in his office in Dunedin after being invited to come to Upper Clutha in 1980. I noticed a photograph on his office wall of a warship at full speed. Peter noticed my interest, but was taken aback when I was able to identify the class of ship as a “Tribal”, a destroyer he served in in the Australian Navy, HMAS “Arunta.” We reminisced, and afterwards he always commented humorously in typical naval humour, that had we still been in the Navy, I would have been his boss; in the Diocese, he was my boss!

His first pastoral visit to Upper Clutha foot got off to a bad start. We had had 2 young nieces staying in the guest room. They had been using the slat bed as a trampoline, and unbeknown to Joan and I, had cracked a couple of slats. Peter sat on the bed, and promptly sank down to the floor. Undaunted, he accompanied me on the normal parish round for that Sunday; Cromwell, Tarras, lunch at Hawea with Dr Mary Tolley, on the Makarora for a service in the school, and then to evensong in Wanaka. One family came over to the Makarora service in a helicopter. Peter said he had never been in a helicopter before, and was treated too his first trip. It made his day.

Peter regarded all his clergy as “family,” and he saw as one of his key tasks the creating and embedding of this sense of family in the Diocese as the shepherd of the shepherds. To this end, the monthly ‘Ad Clerum’ letters helped clergy to keep in touch. To make this more personal, it was his habit to deliver the Diocesan mail, if the envelopes were ready when he was off to the outer reaches of his scattered Diocese. If he was off to Invercargill, for example,he would drop-off the packages at each vicarage en route, arriving unannounced and very informally. Clergy wives would get the episcopal kiss, and he would catch up on what was happening. His philosophy was always that people mattered, because they mattered to God.

He made his last visit to us only 3 weeks before he died. It took great courage, and we shall always remember him for that. A true shepherd and Bishop of our souls.

Stephen White remembers:

I was brought up to be (as a good Anglican in a former time) to be somewhat in awe of bishops who were infrequently seen in humble parish (usually just for confirmations) and with whom as a mere parishioner you never addressed. As I was to discover later when I got to know him, +Peter was nothing like a remote, distant figure. Quite the opposite. But when I first talked to him … well, what could I possibly say to a bishop?

I had applied for ordination and had little idea what the process was. I was at home when the phone rang one morning and I answered to hear Bishop Peter at the other end. I confess that I was so surprised and the call was so unexpected that I dropped the phone which bounced several times against the wall and left me scrabbling to pick it up and thinking. “Well, that’s that.” I apologised and held my breath. I heard a faint chuckle, a very pleasant ‘These things happen”, followed by a request to come into Dunedin so he could meet me. Even after I had hung up I could still not quite believe that the Bishop had rung and even more had overlooked my incredible bungling.

Later, I was to know him better – his warm humanity and his wisdom particularly, and I grew to respect the way that he carried his office with its formal demands and protocols, without losing his ability to relate to people and taking the time to listen.

H Robert Wilson recalls:

+Bishop Peter was an amazing warm, yet unassuming Christian, who related easily to just everyone. He played enthusiastic, even if slightly unpredictable tennis at the Moana Tennis Club with a certain Widow Natalie Ellis. When, after persistent numerous marriage proposals by the Widower, H Robert, she finally conceded defeat, Natalie was firm that that +Bishop Peter could be persuaded to come out of retirement to conduct our marriage at St. Michaels & All Angels in Andersons Bay. Knowing us both well, he peremptorily and enthusiastically brushed aside any thought that we needed any spiritual counselling and presided at a most relaxed & joyful occasion. We were so blessed to enjoy his and Ann’s friendship.

Bishop Penelope Ann Banstall Jamieson

1990 – 2004

English-born New Zealander Penny Jamieson was the first woman in the world to be ordained a Diocesan Bishop of the Anglican Church.

While Vicar of St Philip’s in Karori, Penny was nominated by a group of women for the position of Bishop of the Anglican Diocese of Dunedin. She was consecrated in 1990, and some criticised the sudden promotion, foreshadowing opposition from the church’s conservative element that would cloud her 14 years in the role. Penny Jamieson retired in June 2004, and was made a distinguished companion of the New Zealand Order of Merit soon after

More Information

The following is from an article in NZ History on Bishop Penny written by Emma Brewerton.

English-born New Zealander Penny Jamieson was the first woman in the world to be ordained a Diocesan Bishop of the Anglican Church.

While Vicar of St Philip’s in Karori, Penny was nominated by a group of women for the position of Bishop of the Anglican Diocese of Dunedin. She was consecrated in 1990, and some criticised the sudden promotion, foreshadowing opposition from the church’s conservative element that would cloud her 14 years in the role.

A graduate of the University of Edinburgh, Penny married New Zealander Ian Jamieson and moved to Wellington with him. There she lectured in linguistics at Victoria University, then worked for the Wellington City Mission while completing her doctoral thesis and mothering three young daughters. During this time she developed her vocation, and was ordained into the priesthood in 1985.

A former student protester, and a campaigner for the ordination of women, Penny continued to speak and write about her beliefs during her term as Bishop. Subjects ranged from the war in Iraq and the greed for oil to local moral issues such as the removal of the hearts of children who had died in Greenlane Hospital. However, she rejected the notion that she would use her position to push other people’s agendas, ‘so that I can truly be an agent of the will of God and not a reactionary puppet in the hands of other people’.

Penny published several books including Living at the Edge: Sacrament and solidarity in leadership, which explored her experiences as a woman in a powerful position within a patriarchal institution.

From the start, it was clear the role would bring its challenges. The Anglican Bishop of Aotearoa, the Rt Rev Whakahuihui Vercoe and the Catholic Bishop of Dunedin, the Most Rev Leonard Boyle, boycotted Penny’s ordination. Eight years later she spoke candidly at Kings College, London, saying she wouldn’t wish being a woman Bishop on anyone. ‘The continuingly subtle, even underground power of patriarchy, whether exercised by men or by women, to destroy from a base of self-righteousness is truly appalling.’

This was days before the Lambeth Conference, a 10-yearly international gathering of Anglican bishops, during which a number of delegates held a parallel meeting in protest at the presence of ordained women.

A constant concern for Penny was the role of the church in modern society, and the need to separate spirituality from dogma. She told a conference in 1996, ‘There is a desperate need in every secular society to “remake” the sacred…. without falling into religious literalism, fundamentalism or dogmatic thinking’. It was a theme she returned to at her last Eucharist as Bishop, stating: ‘I still long for a church that can look out and engage with confidence in the society in which we are situated.’

Penny Jamieson retired in June 2004, and was made a distinguished companion of the New Zealand Order of Merit soon after. She expressed regret that she had no-one to ‘pass the mantle on to’. It was not until August 2008 when The Right Reverend Victoria Matthews, a Canadian bishop, became New Zealand’s second woman bishop when she was elected Bishop of Christchurch.

A video of one of Bishop Penny’s Farewell service in Southland (video cover photo was taken at her ordination in 1990)

Bishop George Howard Douglas Connor

2005 – 2009

George Connor was educated at St John’s College, Auckland and ordained in 1966.

He was a Theological Tutor for the Church of Melanesia and then a Maori Mission priest for the Diocese of Waiapu. He was Archdeacon of Waiapu and then Regional Bishop in the Bay of Plenty until 2005 when he was translated to Dunedin. He resigned his episcopal see on 30 November 2009. He is married to Nonie Connor.

See an article in Toanga when Bishop George announced his intention to retire.

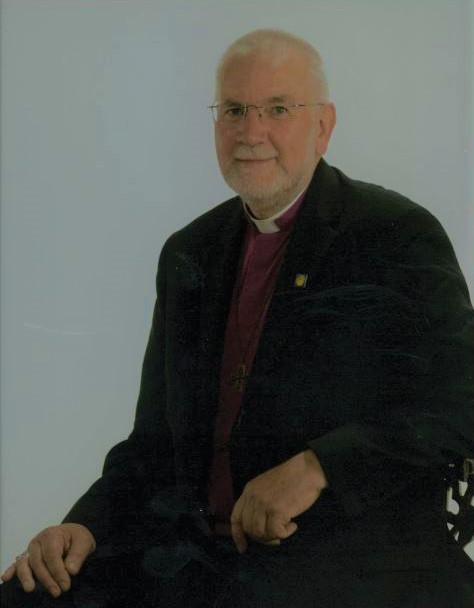

Bishop Kelvin Peter Wright

2010 – 2017

Kelvin Wright was the ninth Anglican bishop of the Diocese of Dunedin in Dunedin, New Zealand. Bishop Kelvin retired on Easter Monday 2017.

He was educated at St John’s College, Auckland, the University of Canterbury, the University of Otago and the San Francisco Theological Seminary. Kelvin was ordained Deacon in 1979, Priest in 1980 and Bishop in 2010. He served as Curate at Merivale and as Vicar of Waihao Downs, Hillcrest, Sumner Redcliffs and St John’s Roslyn.

Kelvin is currently engaged in a very “active retirement”, serving as a Regional Facilitator for Anglican Schools of Aotearoa New Zealand and Polynesia, as well as continuing to lead worship and act as a spiritual director. He lives in Dunedin and is married to Clemency.

Bishop Steven Benford

2017 – May 2024

Steven (Steve) Benford is the tenth Bishop of Dunedin, ordained and installed on 22 September 2017.

Since October 2014, he had been the Vicar of The Church of St. Joseph the Worker, Northolt in West London. In the Diocese of London, he was also a bishop’s adviser for ministry, a new incumbent’s ministry mentor and spiritual director.

Steve has pursued a double career, for many years having worked as a doctor, having specialised as an anaesthetist working in the north of England, then in New Zealand, and then back in the North of England. After 6 1/2 years he is due to finish at the Diocese of Dunedin on 19 May 2023 and is planning to return to the UK with his wife Lorraine.

Diocese of Dunedin Timeline

Have a look at our timeline...

1814 |

Gospel first preached in Aotearoa at Oihi, Northland by Anglican Missionary Samuel Marden |

1840 |

Gospel first preached in the South Island at Karitane by Methodist Missionary James Watkin |

1841 |

George Selwyn consecrated and appointed Bishop of NZ (including Polynesia and Melanesia) |

1843 |

First Anglican missionaries to Southland and Otago: Tamihana Te Rauparaha and Matene Te Whiti |

1852 |

John Fenton arrives in Dunedin, first Anglican Priest to settle south of Lyttleton |

1856 |

Diocese of New Zealand subdivided, Southland and Otago included in the Diocese of Christchurch |

1857 |

Constitution of The Branch of the United Church of England and Ireland in New Zealand signed |

1866 |

Henry Jenner selected and ordained by the Archbishop of Canterbury “into the office of a Bishop of the United Church of England and Ireland in the colony of New Zealand”, with the intention that he be Bishop of Dunedin |

1869 |

Diocese of Dunedin formed from the Diocese of Christchurch, the first meeting of Dunedin’s Synod rejected Jenner’s claim to the See. |

1871 |

Samuel Nevill enthroned as Bishop of Dunedin |

1920 |

2nd Bishop, Issac Richards |

1934 |

3rd Bishop, William Fitchett |

1953 |

4th Bishop, Allen Johnston |

1969 |

5th Bishop, Walter Robinson and Centenary of the Diocese |

1976 |

6th Bishop, Peter Mann |

1983 & 1984 |

Claire Brown, first woman ordained Deacon and Priest in Diocese |

1989 |

A New Zealand Prayer Book/He Karakia Mihinare o Aotearoa published |

1989 |

7th Bishop, Penny Jamieson, first female Diocesan Bishop in the Anglican Communion |

1992 |

Revised constitution for the Anglican Church in Aotearoa, New Zealand and Polynesia/Te Hahi Mihinare ki Aotearoa ki Niu Tireni, ki Nga Moutere o Te Moana Nui a Kiwa |

1992 |

Te Hui Amorangi o Te Wai Ponamu established |

2005 |

8th Bishop, George Connor |

2010 |

9th Bishop, Kelvin Wright |

2017 |

Tenth Bishop, Steven Benford |

2019 |

Sesquicentennial of the Diocese |

Some More History

Most of historical information is kept in our various archives, but we have some items of interest in the Diocesan Office

Images from Green Island